Mass incarceration in the United States has been touted as a solution to crime, yet the evidence overwhelmingly suggests otherwise. A recent report from The Sentencing Project details how the rhetoric that locking more people up makes communities safer isn’t based in facts. The truth on crime reduction is more nuanced and a closer look at mass incarceration shows that the results are often counterproductive.

The roots of mass incarceration trace back to policies enacted in the 1990s, driven largely by fears of rising crime rates. This led to a dramatic increase in incarceration rates, particularly affecting Black Americans, without delivering the promised benefits in terms of community safety. Recent legislative shifts, such as New York's bail reform reversal and Louisiana's harsher sentencing laws, reflect a resurgence in punitive measures that threaten to undo the modest gains made in reducing the prison population.

One key flaw in mass incarceration has been the failure to address the root causes of crime. The War on Drugs disproportionately targeted minority communities while neglecting treatment for substance abuse, mental health, and poverty. Instead of reducing crime, “tough-on-crime” policies have perpetuated cycles of impoverishment and incarceration. Lengthy sentences often keep individuals behind bars much longer than their peak crime-committing years, with little evidence to suggest this approach deters future criminal behavior. Studies indicate that criminal careers typically peak and decline within a relatively short period, generally within a decade.

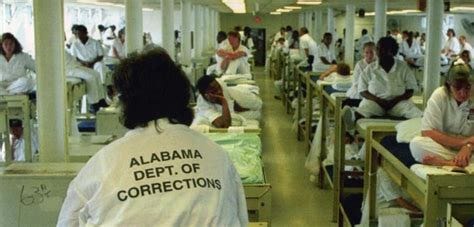

This is seen in Alabama, where the prison system is being sued by the Department of Justice for dangerous conditions including overcrowding. Organizations such as the Alabama Justice Initiative have been formed to push for better solutions. “One of the things we really pushed for last year was elderly and infirmed people having the eligibility to be released based on their age and/or the severity of the illness,” shares Deputy Director Veronica Johnson, “The average life expectancy for a person that is currently housed in the Alabama Department of Corrections is 64 years old. I want us to use more quantitative, scientific research to determine how sentences should be given—coupled with individuality. We can’t use a cookie cutter approach in sentencing. I get the grid and how it’s supposed to work but it’s failing a whole system of people.”

The resurgence of punitive policies in recent years threatens to reverse the progress made in reducing incarceration rates and addressing systemic inequalities in the criminal justice system. Rather than doubling down on failed strategies from the past, policymakers must prioritize evidence-based approaches that address the underlying causes of crime. By investing in rehabilitation, mental health services, and social support systems, communities can foster genuine safety and well-being without resorting to the costly and ineffective measures of mass incarceration.

One look at how this more community-centric approach to reducing crime could take shape is found at The Beacon Center in Montgomery, Alabama. Pastor Richard Williams of the Metropolitan United Methodist Church has formed a resource hub to assist underserved communities with basic needs and life-improvement programs. The Center’s Next Steps program combats generations-worth of inequities with direct resources and investments in the surrounding neighborhoods. Support provided includes job programs, mentorship/support networks, GED preparation, educational programs, food pantries, mental health resources, substance abuse programs, and more.

While the statistics show us that mass incarceration isn’t the solution to reducing crime, it is our job to find the answers that do. Fortunately, Alabama organizations are already doing the hard work. All we have to do is follow the lead of organizations such as the Alabama Justice Initiative and Beacon Center as they imagine more fulfilling solutions.